from the book A Primer on Communication Studies

by Andy Schmitz

Sound Mass Media

The origins of sound-based mass media, radio in particular, can be traced primarily to the invention and spread of the telegraph.Richard Campbell, Christopher R. Martin, and Bettina Fabos, Media & Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: Bedford St. Martin’s, 2007), 113. The telegraph was invented in the 1840s and was made practical by Samuel Morse, who invented a system of dots and dashes that could be transmitted across the telegraph cable using electric pulses, making it the first nearly instant one-to-one communication technology. Messages were encoded to and decoded from dots and dashes on either end of the cable. The first telegraph line ran between Washington, DC, and Baltimore, Maryland, in 1844, and the first transcontinental line started functioning in 1861. By 1866, we could send transatlantic telegraphs on a cable that ran across the ocean floor between Newfoundland, Canada, and Ireland. This first cable could only transmit about six words per minute, but it was the precursor to the global communications network that we now rely on every day. Something else was needed, though, to solve some ongoing communication problems. First, the telegraph couldn’t transmit the human voice or other messages aside from language translated into coded electrical pulses. Second, anything not connected to a cable—like a ship, for instance—couldn’t benefit from telegraph technology. During this time, war ships couldn’t be notified when wars ended and they sometimes went on fighting for months before they could be located and informed.

Wireless Sound Transmission

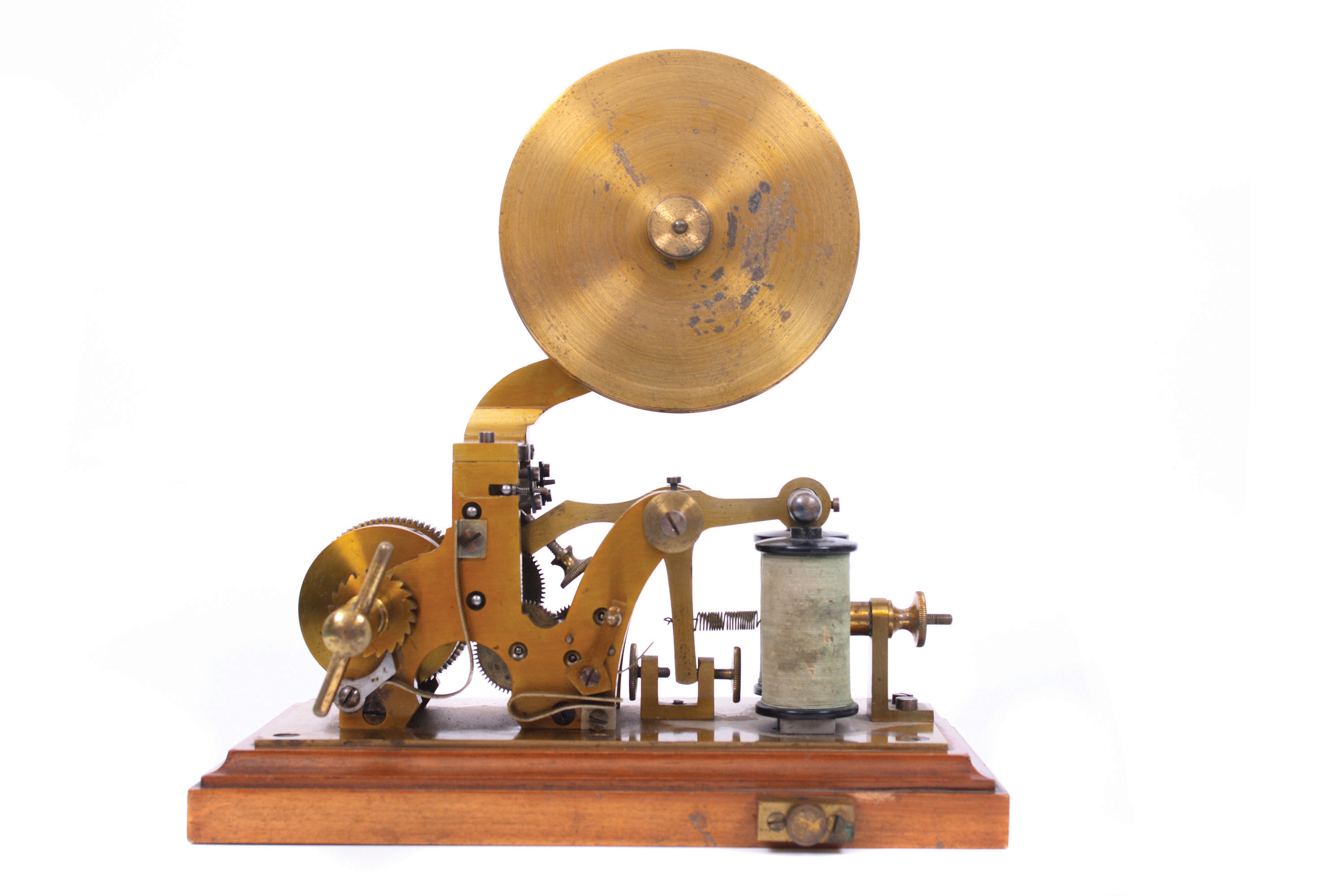

As the telegraph was taking off around the world, the physicist Heinrich Hertz began to theorize about electromagnetic energy, which is measurable physical energy in the atmosphere that moves at light speed. Although Hertz proved the existence of this energy all around us in the atmosphere, it was up to later inventors and thinkers to turn this potential into a mass medium.John R. Bittner, Mass Communication, 6th ed. (Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1996), 159. Hertz’s theories fascinated Italian-born Guglielmo Marconi, who in his late teens began capitalizing on Hertz and others’ theories of electromagnetism to inform and further his own experiments. By 1895 his work had enabled him to send a wireless signal about a mile and a half. With this, the wireless telegraph, which used electromagnetic waves to transmit signals coded into pulses and was the precursor to radio, was born. Marconi traveled to England, where he received a patent on his wireless telegraph machine in 1896. By 1901, Marconi successfully sent a wireless message across the Atlantic Ocean. Marconi became extremely successful, establishing companies in the United States and Europe and holding exclusive contracts with shipping companies and other large businesses. For example, the Marconi Telegraph Company had the communications contract with White Star Lines and was responsible for sending the SOS call that alerted other ships that the Titanic had struck an iceberg. For years, Marconi essentially had a monopoly on the transmission of wireless messages. His success at adapting the already existing system of Morse code to wireless transmission was apparently satisfying enough that Marconi showed little interest in expanding the technology to transmit actual sounds like speech or music.

Although the wireless telegraph machine was the forerunner to radio broadcasting, its inventor did not envision the possibility of sending speech or music instead of Morse code.

© Thinkstock

After Marconi, the road to radio broadcast and sound-based mass media was relatively short, as others quickly expanded on his work. As is often the case with rapid technological advancement, numerous experiments and public demonstrations of radio technology—some more successful than others—were taking place around the same time in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This rapid overlapping development has created debate over who first accomplished particular feats. Although working separately, Nathan B. Stubblefield, a melon farmer from Kentucky, and Reginald A. Fessenden, a professor from Pittsburgh, paved the way for radio as a mass medium when they broadcast speech and music over a wireless signal in the 1890s.John R. Bittner, Mass Communication, 6th ed. (Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1996), 160. Although these men were able to transmit weather updates and music, their equipment was much too large and complicated to attract a mass of people eager to own it. Inventions by J. Ambrose Fleming and Lee de Forest paved the way for much more controlled and manageable receivers. Lee de Forest, in particular, was interested in competing with Marconi by advancing wireless technology to be able to transmit speech and music. Despite the contributions of the other inventors mentioned before, de Forest patented more than three hundred inventions and is often referred to as the “father of radio” because of his improvements on reception, conduction, and amplification of the signals—now including music and speech—sent wirelessly. His improvements on the vacuum tube made the way for radio and television and ushered in a new age of modern electronics.Richard Campbell, Christopher R. Martin, and Bettina Fabos, Media & Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: Bedford St. Martin’s, 2007), 116–17.Since the technological advances that paved the way for radio and television happened during this time, we can mark this as the beginning of the “audiovisual age” that spanned the years from 1850 to 1990.Marshall T. Poe, A History of Communications: Media and Society from the Evolution of Speech to the Internet (New York: Cambridge, 2011), 168.

The Birth of Broadcast Radio

As the technology became more practical and stable, businesses and governments began to see the value in expanding these devices from primarily a point-to-point or person-to-person application to a one-to-many application. It wasn’t until 1916 that David Sarnoff, a former Marconi telegraph operator, proposed making radio a household necessity. He suggested that his new employer, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), invest in a household radio that contained all the necessary parts in one box. His pitch was made more appealing by his suggestion that such a device would make RCA a household name and attract national and international attention.John R. Bittner, Mass Communication, 6th ed. (Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1996), 161.

Sarnoff’s plan to make radio a centerpiece of nearly every US American household was successful, and the still relatively new medium of sound transmission was on its way to becoming the primary means of entertainment and information for many. With the technology now accessible, other key elements of radio as a mass medium like stations, content, financing, audience identification, advertising, and competition began to receive attention.

Timeline of Developments in RadioThomas H. White, “United States Early Radio History,” accessed September 15, 2012, http://earlyradiohistory.us.

- 1909. First commercial radio station signs on the air as an experimental venture by Dr. Charles David Herrold in San Jose, California, which he primarily uses to advertise for his new School of Radio.

- 1919. First noncommercial radio station goes on the air at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- 1920. KDKA, the station often credited as signaling the beginning of the age of commercial broadcast radio, receives financial backing from Westinghouse (a major company) and gains much national attention for airing election returns following the 1920 presidential election.

- 1921. The US Commerce Department licenses five radio stations.

- 1922. The first broadcasting network is created by New York station WEAF to give advertisers a discount and allow them to reach a larger audience at once.

- 1923. More than 600 commercial and noncommercial radio stations are in operation and about 550,000 radio receivers have been sold to US consumers.

- 1925. 5.5 million radios are now in use in the United States, making radio a powerful mass medium.

- Late 1920s. The National Broadcasting Company (NBC), the largest radio network, begins to form affiliate relationships with independent stations that will broadcast NBC’s content to supplement their own programming (a practice that is still used today by radio and television networks). The network/affiliate model allows major networks to concentrate news broadcasting, acting, singing, and technical talent in one place and still have that programming reach people all over the country, which saves time and money.

- 1927. 25–30 million people listen to a “welcome home party” for Charles Lindbergh, who had just completed the first solo transatlantic flight, making it the largest shared audience experience in history until that point.

How Radio Adapted to Changing Technologies

The 1920s boom in radio created problems as radio waves became so crowded that nearly every radio had poor or sporadic reception. The Radio Act of 1927 and the Federal Communications Act of 1934 helped establish some order and guidelines for frequency use and created a policy that stated any broadcaster using the now government-owned airwaves had to act in the public’s interest. As reception became more reliable, programming content became more diverse to include news, dramas, comedies, music, and quiz shows, among others, and radio entered its “golden age.” During the 1930s and 1940s, the radio was the center of most US American families’ living rooms. Later, as television began to replace the radio as the central part of home entertainment, radio was forced to adapt to the changing marketplace.Richard Campbell, Christopher R. Martin, and Bettina Fabos, Media & Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: Bedford St. Martin’s, 2007), 125–45. For example, during the 1950s, radio technology had advanced to the point that it could now be made portable. Since radio was being forced outside the home, radio capitalized on its portability by marketing pocket-sized transistor radios that could go places television could not. Radio also partnered with car manufacturers and soon became a standard feature in new automobiles, something that was very uncommon before the 1950s. Radio also turned to the music industry to replace the content it had lost to television. Stations that once aired prime-time dramas and comedies now aired popular music of the day, as the “Top 40” format that played new songs in a heavy rotation was introduced. Talk radio also began to grow as radio personalities combined the talk, news, traffic, and music formats during the very popular and competitive “drive time” hours during which many people still listen to the radio while traveling to and from work or school. Even more recently, radio stations have turned to online streaming and podcasts so their content can still make its way to computers and portable devices such as smartphones. Just as radio caught on quickly, however, so did television and movies. In the end, the combination of audio and visual offered by these new media won out over radio.

No comments:

Post a Comment